Disclaimer: the theories postulated in the following article are far too ridiculous to be accurate. In reality, Nike had about as much to do with the US Postal Service Pro Cycling Team’s doping regime as the Looney Tunes had to do with Michael Jordan’s return to basketball. The connections, however, are obvious.

Part 1: The Beginning Of The End

Sophisticated, professionalised and successful

On October 10th 2012, the United States Anti-Doping Agency released a 1000 page document detailing “the most sophisticated, professionalised and successful doping programme that sport has ever seen”. The programme in question is that of the US Postal Service Pro Cycling Team who, between 1999 and 2005, supported team captain Lance Armstrong to a record seven consecutive Tour de France titles.

For over two decades, despite the numerous allegations of doping from team members and journalists, Lance Armstrong constantly and defiantly refuted claims that he had cheated his way to every single one of his seven yellow jerseys. USADA’s report, however, is undeniable proof that Lance Armstrong, as well as every other member of the US Postal Service Team, was under the influence of performance enhancing drugs during each Tour de France victory.

Finally, in January 2013, Armstrong admitted to doping in an interview with Oprah Winfrey. At the start of the interview, he was asked to simply answer ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to each question.

Oprah Winfrey asks, “Yes or no, did you ever take banned substances to enhance your cycling performance?” Lance Armstrong responds “Yes.” Oprah again, “Yes or no, was one of those banned substances EPO?” Lance Armstrong, again, responds in the affirmative. Oprah continues: “Did you ever blood dope or use blood transfusions to enhance your cycling performance?”

“Yes.”

“Did you ever use any other banned substances like testosterone, cortisone or Human Growth Hormone?”

“Yes.”

“Yes or no, in all seven of your Tour de France victories, did you ever take banned substances or blood dope?”

“Yes.”

There are a number of explanations as to why Armstrong was so quick to disagree with USADA: perhaps he wanted to downplay the amount of substance abuse that went on in the team; perhaps he wanted to protect the as-yet relatively unsullied cyclists he rode alongside; perhaps he wanted to protect himself against further demonization. Or, perhaps, there was a far more sinister reason behind his denial: he wanted to protect himself against the men who had orchestrated his victories in the first place; the shadowy figures who propelled Armstrong to the top and then, just as quickly, let him fall all the way to the bottom; the organisation who had exposed Armstrong, early on in his career, to the greatest doping guide of the 20th Century. The guide is a film: a brilliant how-to, exposing and explaining how a sportsman can guarantee victory, even from the jaws of certain defeat. It is eighty-eight minutes of unsurpassed cryptography, overloaded with hidden messages that even the greatest conspiracy theorists are yet to fully unravel.

That is, until today…

The beginning of the end

The early 1990s. Lance Armstrong, a champion triathlete despite his tender years, has just made the transition to cycling. In 1992, he signs his first professional contract with Motorola. No longer a boy, he would not have noticed a commercial aired on American TV which featured Bugs Bunny and Michael Jordan bossing it on the court courtesy of their Nike Air Jordans. Only a year later, Armstrong wins his first big title. Early on in that same year, he sits down in front of the television with the rest of the United States of America to watch the Dallas Cowboys win Super Bowl XXVII. He barely notices a halftime commercial, in which Bugs Bunny and Michael Jordan team up again, this time to compete with a group of Martians for the World’s supply of Nike Air Jordans. The seed has been sown…

Two months later, tragedy strikes. Armstrong is diagnosed with stage three testicular cancer, cancer which has spread to his heart and his lungs. Although immediate chemotherapy and surgery to remove the diseased testicle save his life, doctors still give Armstrong less than a 50% chance of survival. Against the recommendations of his doctor, Armstrong decides on a cocktail of medications excluding Bleomycin, a drug connected with lung inflammation. The decision saves his career.

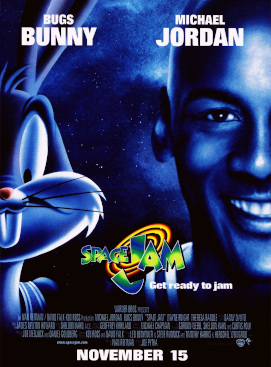

Battling cancer for five months, Armstrong barely notices the release of an inspirational sports movie in November 1996, which chronicles the return of one of the greatest basketball players of all time. The film, a collaboration between Warner Brothers most renowned characters and Nike’s star player, is a box office success, opening #1 in the US and grossing $230 million worldwide. Its name: Space Jam.

In February 1997, Armstrong beats his cancer. Desperate to get back to cycling, Armstrong is dealt a severe blow when he learns that his Cofidis Cycling contract has been cancelled. Without a team and struggling for full fitness, Armstrong is at his lowest point since his diagnosis. However, his fight against cancer has earned him the recognition and admiration of millions of people worldwide. He signs a contract with the US Postal Service Pro Cycling Team and begins training.

In February 1997, Armstrong beats his cancer. Desperate to get back to cycling, Armstrong is dealt a severe blow when he learns that his Cofidis Cycling contract has been cancelled. Without a team and struggling for full fitness, Armstrong is at his lowest point since his diagnosis. However, his fight against cancer has earned him the recognition and admiration of millions of people worldwide. He signs a contract with the US Postal Service Pro Cycling Team and begins training. Armstrong, however, is a changed man. The never-say-die, win-at-all-costs attitude he cultivated during his battle with cancer has stayed with him: he has become willing to do anything in order to win the Tour. It is an attitude that attracts the attention of one of the biggest brands in the world, a brand which only backs the winning stallion, a brand which knows the secret to guaranteeing victory.

That brand is Nike.

Unity is strength, knowledge is power and attitude is everything

Although we will never know exactly when Nike’s shady sponsorship executives revealed Space Jam’s secrets of success to Lance Armstrong, we can speculate.

In 1997, Armstrong was at an all-time high: he had signed a new pro cycling contract, he was training hard to participate in 1998’s Tour de France and he had beaten cancer. He wanted to give something back to the agents of fortune who had ensured his survival: he wanted to raise awareness of cancer and to give hope to other sufferers. Armstrong decided to set up the Lance Armstrong Foundation, a charity with the motto “Unity is strength, knowledge is power and attitude is everything.”

Nike were already the kit sponsors of the US Postal Service Pro Cycling Team, so it is easy to say that they must have had some involvement in signing Armstrong. We can, however, only speculate as to whether or not Nike promised Armstrong the support he received from them 7 years later.

Nike were already the kit sponsors of the US Postal Service Pro Cycling Team, so it is easy to say that they must have had some involvement in signing Armstrong. We can, however, only speculate as to whether or not Nike promised Armstrong the support he received from them 7 years later. In 2004, the representatives of sportswear brand Nike approached Armstrong, offering him a lucrative sponsorship deal, as well as the help he needed in creating a ground-breaking campaign to promote his new foundation: the Livestrong wristband. Over the next decade, 80 million bracelets were sold and over $500 million was raised.

What we can say for certain is that, before their surprise victory in 1999, Lance Armstrong and the rest of the US Postal Service Pro Cycling team were indoctrinated into the Space Jam philosophy of certain victory, a philosophy echoed by the Lance Armstrong Foundation: “unity is strength, knowledge is power and attitude is everything”.

0 comments:

Post a Comment